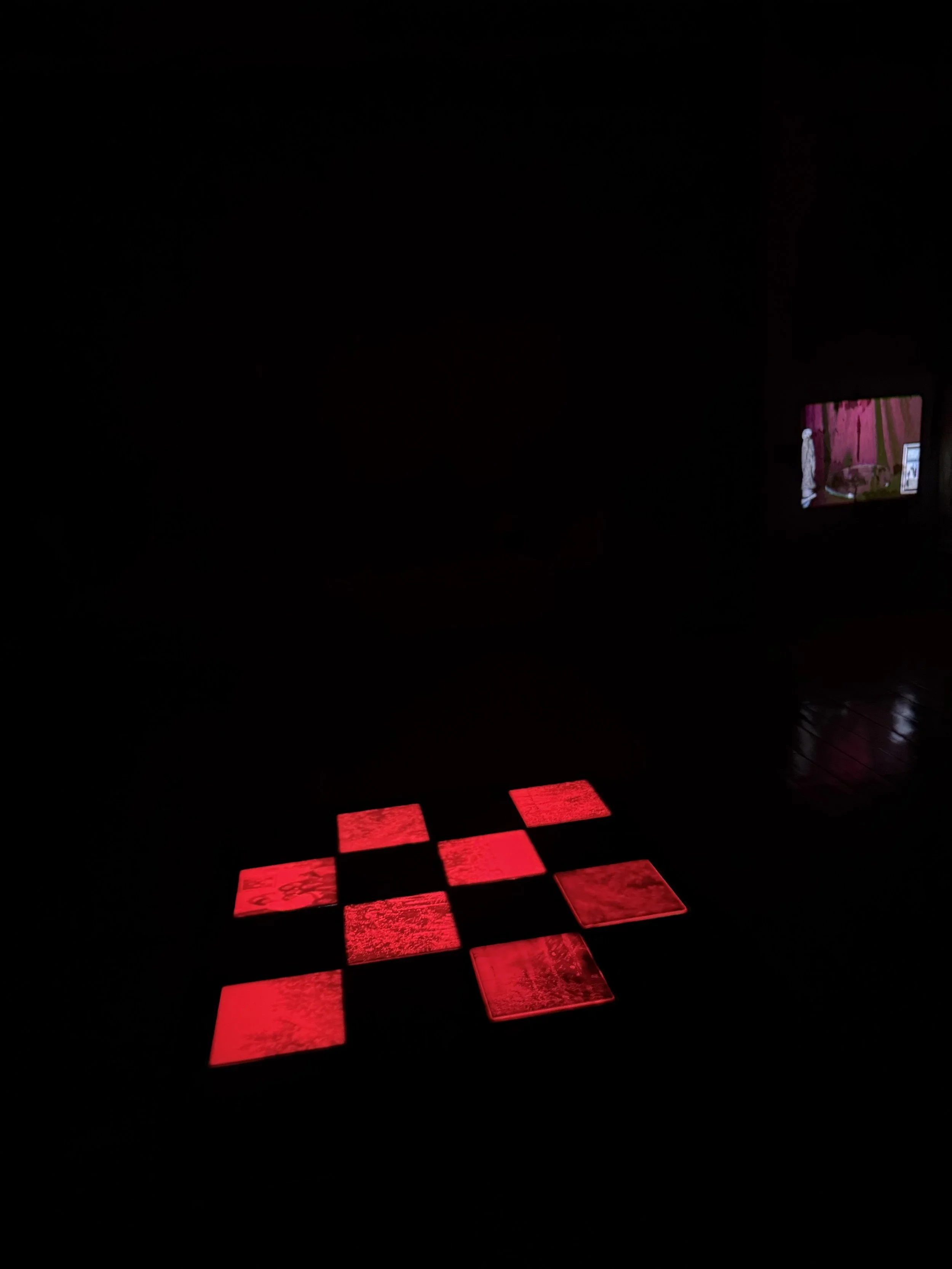

The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

August 2 – September 13, 2025

As the Sun crossed the horizon early on Sunday mornings, the clubgoers at the Kinloch Cotton Club made their way across the parking lot and into the rows of pews organized in neat columns flanking either side of the small yet beautiful sanctuary of First Missionary Baptist Church of Kinloch. Existing on opposing sides of their shared block on the western edge of town, the two would exchange populations as night gave way to morning, and one week transitioned into another. The land that contained them is now vacant, and the buildings that once provided space for secular Saturday nights and sacred Sunday mornings are long gone. Some traces of the past continue to linger. The ground still holds the traces of patterned footsteps that marked both praise and worship. The air, full of breath, deep exhales, and waning shouts.

The spatial relationship between these two environments offers an opportunity to consider the conditions under which new practices and rituals are formed within Black communities—especially in the context of the post-industrial Midwest. Black people's ties to the Great Migration, which significantly reshaped cities across the Midwest (and especially St. Louis), create a historical throughline that informs these emergent forms of expression and spiritual life.

This work interrogates how such practices might counter the omnipresent histories of racial violence and dispossession—histories that persist alongside, and often in tension with, sacred Black practices. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it is an immersive installation that examines the metaphysical properties of Black space. Through the use of light, archival material, new imagery, and experimental video, the installation gathers and enacts the potential forms that new ritualistic practices might take and hold.

This body of work intentionally considers the role of spirit in resisting the erasure and illegibility produced by discriminatory urban planning. At the same time, it acknowledges the deep impact of these harmful practices on the emergence of fugitive, racialized spiritual traditions. These acts of refusal—of remembering, of ritual-making—persist both within and beyond the boundaries imposed on Black neighborhoods and towns.

And, despite the boundaries—commonly known as redlining—that confine and attempt to excise Black cultural and spiritual life, new practices always emerge. These rituals serve as forms of resistance. They are also acts of sacred creation: practices that affirm presence, history, and metaphysical possibility in the midst of imposed absence.

-Shabez Jamal

‘Shabez Jamal Illuminates Black Histories at SHED Projects’

A review by Zara Yost